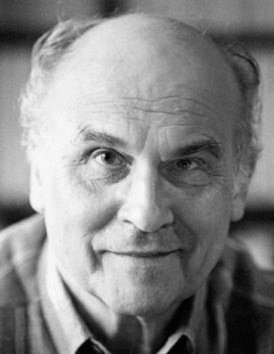

Ryszard Kapuscinski

Victoria Brittain, The Guardian,

Ryszard Kapuściński

Image: photographer unknown

The master of literary reportage: ‘A journalist has to first be a good human being.’

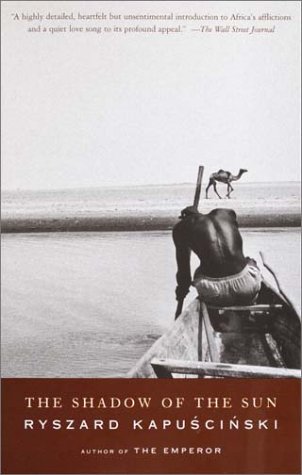

Kapuscinski shared his open point of view and his discoveries as a curious person. His stories about coups and wars in Africa during the 2nd half of the 20th century, aren’t full of misery. Kapuscinski was a bestselling writer, respecting the dignity and soul of African people. He shared people’s stories about their lives and the cultural diversity of the continent. As a Polish reporter with a low travel budget, he himself played a role within the stories he wrote as well. Becoming a welcomed guest, instead of a passing reporter in search for a ‘quick’ story on site. Thousands of people worldwide are still reading his books like ‘Shadow of the Sun’, in which Ryszard Kapuscinski witnessed the beginning of the end of colonial rule around 1960. To me, it doesn’t matter what is fiction or fact, what matters is that his reports touch the minds and awareness of people. And won’t be forgotten.

‘The experience was an exciting one for me. It illustrated that writing was about risk – about risking everything. And that the value of the writing is not in what you publish but in its consequences. If you set out to describe reality, then the influence of the writing is upon reality.’

– Ryszard Kapuściński (1932 – 2007)

Image: Lidia Puka (daughter of R.K.)

–

Video Ebano

‘A tribute to the masterpiece of Ryszard Kapuscinski “Ebony”. The difference between European’s and African’s time has feedback on the lifestyles that these two populations, very different, have. The time in Europe is very marked, it is thought of as a large circular structure that keeps track of time like a clock with precision, without mistakes, and with an infinite and inexorable trend. The time in Africa is much more elastic, it is thought of as an entity capable of being able to move in space and to be able to change shapes and colors that want. It has a more personal, and highly dependent on the person.’

– Ebano, video & design by Guido Chiefalo

–

The ‘magical realism’ of the now-departed master

By Jack Shafer, Jan. 25, 2007. Source: Slate.com

…Scratch a Kapuściński enthusiast and he’ll insist that everybody who reads the master’s books understands from context that not everything in them is to be taken literally. This is a bold claim, as Kapuściński’s work draws its power from the fantastic and presumably true stories he collects from places few of us will ever visit and few news organization have the resources to re-report and confirm. If Kapuściński regularly mashes up the observed (journalism) with the imagined (fiction), how certain can we be of our abilities to separate the two while reading?…

Ryle quotes a 2001 interview in the Independent, in which Kapuściński complains about the excess of “fables” and “make-believe,” saying, “Journalists must deepen their anthropological and cultural knowledge and explain the context of events. They must read.” …In a 1987 interview in Granta,he speaks disdainfully of journalistic conventions, saying:

–

For Ryszard Kapuscinski, who has died aged 74, journalism was a mission, not a career, and he spent much of his life, happily, in uncomfortable and obscure places, many of them in Africa, trying to convey their essence to a continent far away. No one was more surprised than him when, in his mid-40s, he suddenly became extremely successful, with his books translated into 30 languages. He won literary prizes in Germany, France, Canada, Italy, the US, and was made journalist of the century in Poland.

Kapuscinski was born in Pinsk, now in Belarus, and in 1945 was taken to Poland by his mother, searching for his soldier father. War as the norm for life was deep in his young psyche after those early years of ceaseless hunger, cold, sudden deaths, noise and terror, with no shoes, no home, no books in school. Decades later he wrote: “We who went through the war know how difficult it is to convey the truth about it to those for whom that experience is, happily, unfamiliar. We know how language fails us, how often we feel helpless, how the experience is, finally, incommunicable.”

After university in Warsaw, where he studied history, he found his metier as a 23-year-old trainee journalist on a youth journal. A story exposing mismanagement and drunkenness in a showcase steel factory set off a political firestorm that sent him into hiding. He was vindicated and sent abroad as a treat, to India, Pakistan and Afghanistan, the first Polish journalist to have that opportunity. Later he moved to the Polish News Agency (PAP), and stayed there until 1981.

In 1957 he went to Africa, and returned there as often as possible over the next 40 years. He covered the whole continent, including 27 revolutions and coups, and was exhilarated by the feeling he was in at history in the making. He and his employers had no money, but he was a deal maker who often had the contacts to help other journalists who did have the money to hire planes, and thus both arrived at the scene of the latest drama. “Africa was my youth,” he said later, describing how much the continent had meant to him.

In his early years as a journalist he developed the technique of two notebooks: one allowed him to earn his living with the bread and butter of agency reporting of facts, while the other was filled with the experiences he too modestly believed incommunicable, but which became his famous books, such as The Emperor (1978), on the fall of that extraordinary figure Haile Selassie of Ethiopia. It was his first book to be translated into English, and Jonathan Miller adapted it for the Royal Court Theatre in 1985.

Before The Emperor, he wrote perhaps his best book, Another Day of Life (1976), a unique and closely observed account of the collapse of Portuguese colonialism in Angola, which he described as “a very personal book, about being alone and lost”. He was the only foreign journalist, and the only person from eastern Europe, in Luanda in the chaotic and fearful summer of 1975. As the Portuguese settlers piled their lives into boxes at the port, soldiers from apartheid South Africa, Zaire and Cuba moved towards the capital in front of or behind the competing Angolan armies, while shady men from the CIA and the Portuguese PIDE fed rumours of imminent triumph for one side or the other.

Amid the unbelievable stories, the heat, the hysteria, the only thread of certainty in Kapuscinski’s days was the evening telex connection with Warsaw, when he would file a story he had concocted from the rumours and the crazy scenes on the street, ask about the weather at home, and complain about the food. He never got that Angola out of his mind, and when we met in London in 1986 he wanted mainly to talk about another book from that period, the Portuguese soldier Antonio Lobo Antunes’s South of Nowhere, which he thought was wonderful.

Among his other books was Shah of Shahs (1982), on the last days of the Shah of Persia, and collections such as The Soccer War (1978), The Shadow of the Sun (1998) and, closer to home, Imperium (1993), essays and reportage on the Soviet Union, and five volumes of essays and poems, Lapidarium. A sixth was due to be published soon.

All his writing about developing countries came out of his lived experience there. It was the ring of authenticity that made him as popular among African and Latin American intellectuals as at home in Poland. They all recognised his portraits of the mechanism of dictatorial rule, as well as appreciating his ease and empathy with ordinary people’s lives. The Polish film-maker Andrzej Wajda made him his model for the journalist in his film Rough Treatment (1978).

Kapuscinksi described his own work as “literary reportage”. And, although he was personally a modest man, he believed in its importance for understanding the world. “Without trying to enter other ways of looking, perceiving, describing, we won’t understand anything of the world.” The European mind, he believed, was often too lazy to make the intellectual effort to see and understand the real world, dominated by the complex problems of poverty, and far away from the manipulated world of television.

The quiet and stability of Europe bored him, and in the last years of his life he spent a considerable amount of time lecturing in Mexico, often with his friend Gabriel García Márquez. He spoke always about the importance of reportage, and delivered stinging attacks on news as a commodity, and on the flying “special correspondents” who report on instant drama without context or follow up. He hated what he called the “metamorphosis of the media”. The value of news in his day, he said, had nothing to do with profits, but was the stuff of political struggle, and the search for truth.

He is survived by his wife Alicja and their daughter.

Jonathan Miller writes: It was a great privilege and very exciting to work with Ryszard Kapuscinski on his magnificent reportage on the last years of Haile Selassie put on at the Royal Court. He told us that he had had several previous requests to make a film set in Ethiopia; but he went on to make it quite clear that it was not really about Ethiopia but about Poland and language. As we rehearsed, it became immediately apparent from the text that he assigned to the various witnesses participating in what we turned into a play that this was an extraordinary representation of ornamental tyranny. I was delighted to discover that he approved of this almost abstract way of representing what he feared might otherwise have been a piece of exotic tourism. He was easy to work with, amiably helpful and, I think, the whole cast enjoyed his reassuring presence. But he was after all a peculiar genius with no modern equivalent, except possibly Kafka.

Adam Low writes: Ryszard Kapuscinski and I made a film together for BBC Arena in 1987. At the time he was writing about Idi Amin and had even drawn a diagram of Amin’s brain, which was pinned on the wall of his small flat in Wola, a working-class district of Warsaw. He had acquired an almost celebrity status in Poland, where his books were read as thinly disguised commentaries on communist Poland. As a person Ryszard was extremely modest and self-effacing. He found the business of filming terribly frustrating (“I am not actor!”), and was so self-conscious in public that I was lucky to get one take before he literally disappeared. He had an inexhaustible number of stories about his experiences in Africa and South America, and a unique ability to focus on the telling object – the key he was given in Moscow to a flat in Azerbaijan, the egg he boiled daily in a kettle at the malaria clinic in Tanzania. He could be very funny, about the pomposity of British colonial officials in West Africa or the grandiosity of the Shah of Iran, and equally chilling about the bodies washed up in Lake Victoria during the final days of Amin.

As a child he had seen Polish partisans being tortured and executed by the Germans in the forests outside Warsaw, but his attitude to humanity was always positive and optimistic. He knew from personal experience that even the most seemingly impregnable dictatorship would eventually collapse.

· Ryszard Kapuscinski, journalist, born March 4 1932; died January 23 2007

Source: http://www.guardian.co.uk/media/2007/jan/25/pressandpublishing.booksobituaries

War Correspondent, Author Ryszard Kapuscinski

By Adam Bernstein, Washington Post Staff Writer

January 25, 2007. Source: Washington Post

Ryszard Kapuscinski, 74, a danger-courting Polish journalist and widely translated author who covered 27 revolutions and was among the most celebrated war correspondents of his generation, died Jan. 23 at Banacha Hospital in Warsaw after a heart attack. He also had cancer.

With prose that was punchy and lyrical, and in which he was often a central figure amid the action, he became a foremost chronicler of the developing world in his books. Likened to a modern-day nomad, he carried only a camera, a clean shirt and money. “The less you have the better for you,” he said, “because to have is to be killed.”

He met the guerrilla fighter Che Guevara in Cuba, political leaders such as Salvador Allende of Chile and prime minister Patrice Lumumba of the Democratic Republic of Congo, and strongmen such as Idi Amin of Uganda.

Famously, he interviewed a former employee of the deposed Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie, a man whose sole duty for 10 years was to use a satin cloth and wipe the shoes of dignitaries soiled by the urine of the emperor’s Japanese dog, Lulu.

Mr. Kapuscinski admitted he could embellish scenes for effect and use composites. His many fans, including John Updike, tended to classify him with Truman Capote as a master of literary nonfiction. One of Mr. Kapuscinski’s book editors linked his atmospheric writing to a tradition of “magical realism” found in Latin American novels that were subjective and blended absurdities with blunt truths.

“Everything is a metaphor,” Mr. Kapuscinski once said. “My ambition is to find the universal.”

During his extensive travels, he could be daring to the point of reckless. This characteristic prompted Salman Rushdie to praise his writing — “an astonishing blend of reportage and artistry” — and to question his friend’s sanity.

At the outbreak of the 1967 Biafran secessionist war in Nigeria, Mr. Kapuscinski heard of a road that was blocked by burning roadblocks and from which “no white man can come back alive.”

Testing the rumor, he passed the first roadblock but was assaulted at a second by machete-wielding thugs who supported the United Progressive Grand Alliance political party. They took his money and doused him with the flammable liquid benzene.

“The boss of the operation stuffed my money into his pocket and shouted at me, blasted me with his beery breath: ‘Power! UPGA must get power! We want power! UPGA is power!'” Mr. Kapuscinski later wrote. “His face was flooding sweat, the veins on his forehead were bulging and his eyes were shot with blood and madness. He was happy and he began to laugh in joy. They all started laughing. That laughter saved me.

“They ordered me to drive on.”

For years, he was little known outside Poland, but his increasing prestige brought him freelance work for the New Yorker, the New York Times Magazine, Granta and other English-language publications. He began writing books in his off-hours, “second versions” of the brief, dreary and highly official dispatches he filed for his day jobs writing for the Polish press.

His books included “The Emperor,” about Selassie’s last days; “The Soccer Wars,” covering military tensions in Latin America and some of his years in Africa; “Another Day of Life,” about Angolan independence from Portugal; “The Shah of Shahs,” about the Iranian revolution; and “Imperium,” about the collapse of the Soviet Union.

He told the Scotsman newspaper after the 1994 publication of “Imperium”: “More philosophically speaking, it’s a book about the uselessness of human sacrifice, in which I’m saying that during the communist time almost 100 million people have been slaughtered and to me this situation, these sufferings and deprivation turn out to be for nothing.

“Nobody is seen to be responsible . . . that human suffering turns out to be useless.”

Mr. Kapuscinski was born March 4, 1932, in Pinsk, an industrial city then in eastern Poland and now in southwestern Belarus. Pinsk was a polyglot of ethnicities, all living side by side and most in desperate poverty. He said life in Pinsk helped him assimilate easily when abroad.

After the Soviet invasion of 1939, the Kapuscinski family moved to a neighborhood near the Warsaw ghetto. He often saw mass executions of Jews. Meanwhile, his father, a schoolteacher, served in the Polish underground.

Ryszard Kapuscinski received a history degree from the University of Warsaw in 1955 and found a reporting job at a Communist journal.

He wrote a highly critical article about a steel factory near Cracow that was officially viewed as a beacon of the Communist ideal. He was fired but then reinstated and decorated by the state when a federal task force exonerated his findings.

Now a star, he persuaded his editors to send him abroad, and for years, he was Poland’s only foreign correspondent. He went to India, then to Ghana to cover its independence from the United Kingdom, then to the Democratic Republic of Congo in time for the coup against Lumumba. He also spent time in Latin America and the Middle East.

Of the Iranian revolution in 1979 that deposed the repressive shah, he wrote: “Revolutions precisely begin when the man has stopped being afraid. He gets rid of his fear and feels free, without that there would be no revolution.” His affiliation with the Solidarity anti-Communist trade union movement in Poland led his government to revoke his press credentials in 1981. Yet he worked regularly from abroad and published many more books, including a praised collection of his African reportage called “The Shadow of the Sun.”

Survivors include his wife of more than 50 years, Alicja Mielczarek, a pediatrician; and a daughter.

For a man of adventure, he was reputed to be surprisingly humble. He shunned bluster when discussing his career. “Empathy is perhaps the most important quality for a foreign correspondent,” he told the New York Times in 1987. “If you have it, other deficiencies are forgivable. If you don’t, nothing much can help.”

Source: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/01/24/AR2007012402233.html