Documentary Art Photography & Intercultural Communication

Her Circle UpClose Interview 2011

Mathilde Jansen: Documentary Art Photography & Intercultural Communication

Published December 1, 2011 (Interview July 2011) | By Beckie Jones | Filed Under: UpClose Interview

Mathilde Jansen’s work is a documentation, exploration and reconstruction of socio-economic, intercultural and environmental developments and occurrences. Through the use of collage and both documentary and staged photography, Jansen juxtaposes reality with fantasy in order to create new perspectives and possibilities both for today and the future and to represent natural, industrial and cultural diversity. These images pose questions to the viewer, in which real and imaginary worlds coexist, and relate to contemporary issues, media representations and inequalities.

Mathilde Jansen’s work is a documentation, exploration and reconstruction of socio-economic, intercultural and environmental developments and occurrences. Through the use of collage and both documentary and staged photography, Jansen juxtaposes reality with fantasy in order to create new perspectives and possibilities both for today and the future and to represent natural, industrial and cultural diversity. These images pose questions to the viewer, in which real and imaginary worlds coexist, and relate to contemporary issues, media representations and inequalities.

Since her teenage years, Jansen has been interested in global media, photography, art and poetry in relation to a sustainable future and intercultural communication. Couple this with periods of working with mentally handicapped people and children, providing her with an insight into human psychological abilities, and you discover where her inspiration was born or, as she puts it, where her “intuitive and adventurous call started”.

Jansen states that it is her aim to “transition towards documentary media (photography and film), capturing culturally interconnected and wondrous daily life realities”. Currently, Jansen lives and works in Amsterdam, The Netherlands but she is working towards a long-term second home in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, with her new family.

Beckie Jones: Tell me more about your work and what first inspired you to look into African, and in particular, Tanzanian economy?

Mathilde Jansen: In 2008 I wondered; what do we know about Africa and what don’t we know from news of development organisations? Why do we hear so little of upcoming African economies in Europe? Most news regarding Africa at this time, covered China’s role as an investor, as if the more commercial approach of a new trade partner in Africa was observed.

Export is the main cause for economical growth. Economy relates to society as a whole; how do people work, collaborate, develop or express themselves? What about infrastructure, commercial and social structures? I wanted to research and portray a politically stable country, so the project would purely focus on its multifaceted economy. Tanzania caught my interest because of its tourism, mining and manufacturing industries; agriculture in areas such as Mount Kilimanjaro; an international trade harbor in the Indian Ocean; an impressive cultural and natural diversity with hot spots such as the Ngorongoro Crater and Serengeti National Park and historical sites representing slave trade together with paradise beaches at Zanzibar. At that time, I had no idea that my life would get interwoven with Tanzania, on both professional and personal levels. I fell in love with Dar es Salaam and one of its citizens, a local and international manager and entrepreneur. It took about eighteen months before we got together and I was ready to embrace the idea of a new future and second home in that country. My photography comes along with me, anywhere I go. So I work a lot in Tanzania and around [the area] portraying economical, intercultural and social life more as an insider. I am interested to show social cross connections between continents, as a part of our post colonial global economy. I can feel and taste a part of Tanzania when I’m in the Netherlands and the other way around, not only in my dreams but by being surrounded by people, materials, food and products.

BJ: It seems to me that you have a very strong message running through your works. To someone who had never seen your work, what would you say that this message is?

Magma (Red and Green) © Mathilde Jansen

MJ: That we, as people, are able to see and create new opportunities and dimensions. I show new viewpoints regarding social, intercultural or sustainable issues and actualities. Touching both real and imaginary or dreamlike worlds, I connect the surreal with the actual world like brother and sister, corresponding to holism in order to question, suggest or point out wondrous realities and the way dreams (don’t) come true. Although through creating these images I gained a strong personal opinion or intuition, I don’t believe that I possess the whole truth and therefore, I maintain an open atmosphere in my images. I am not trying to convince people, I want to inspire people. By playing with both fantastic and real elements in my photography, I question and spread my message ‘dreams come true’. Brotherhood, nature and inner freedom play important roles in my pictures. How can someone preach freedom?

BJ: On your website, you state that “Tanzanians are often considered lower class in their own country. Indians, Chinese, Americans, Europeans and South Africans are usually more successful in business and more powerful.” Why do you think this is?

MJ: We’d need a banker, foreign investor, local entrepreneur, the president, a miner, historian, a journalist, farmer and teacher to get a full picture of this issue. I’m just a photographer from the Netherlands, although I did make some observations.

Those foreign companies usually operate more efficiently, quicker, with better finances and a straight no-nonsense business culture. They also focus on commercial strategies with a main concern ‘what’s in it for me.. and our shareholders?’. As they make more money, they’re more powerful and the other way around.

I think Tanzanian businesses are usually more informally organized, occupied with social and cultural rules and spending time on responsibilities regarding private and professional networks. Those networks are interwoven with many steps, resulting in both corruption and strong solidarity. They operate within more complex circumstances and are financially less capable of solving typical African daily trouble which may be on the way. A broken tyre can’t be repaired immediately or the truck had to be used to take the neighbor to a hospital, for example. This means that the goods will be delayed and may be rotten by tomorrow due to the weather. I believe local businesses depend more on local and social processes, slowing down the speed of activities. Though, the global market is competitive and doesn’t care about your neighbour, the hot weather or a hole in the road.

Coming from the Netherlands, the class system in Tanzania has been a new phenomenon to me. Happily, people do mix well in Dar es Salaam and I feel at home there though I’ve noticed that Tanzanians are often seen as executive staff, servants or as people in need of help. There’s usually a gap between managerial and executive staff. I’ve only seen a few foreign companies with managerial training programs for local staff. This class system is complex. One could blame foreigners who show too little respect for local people of a, so called, “third world country”, but high or middle class Tanzanians sometimes discriminate against lower class Tanzanians as well.

I’d be naive to think I’m able to answer this question, but in my work I’ve been researching this openly. I’ve witnessed hypocrisy. People speaking out loud about having left a wealthy life and job in the USA or elsewhere to work in Tanzania, as if it was a huge sacrifice to help poorer people, whilst sitting in a brand new car, enjoying a sundowner near the beach or commanding a “servant” to bring more tea. I’m sure more westerners – especially those who really work hard or sacrifice to help people – feel just as uncomfortable as me to witness certain situations. It is a tragic illustration of old fashioned power structures. The division among classes is a two way problem.

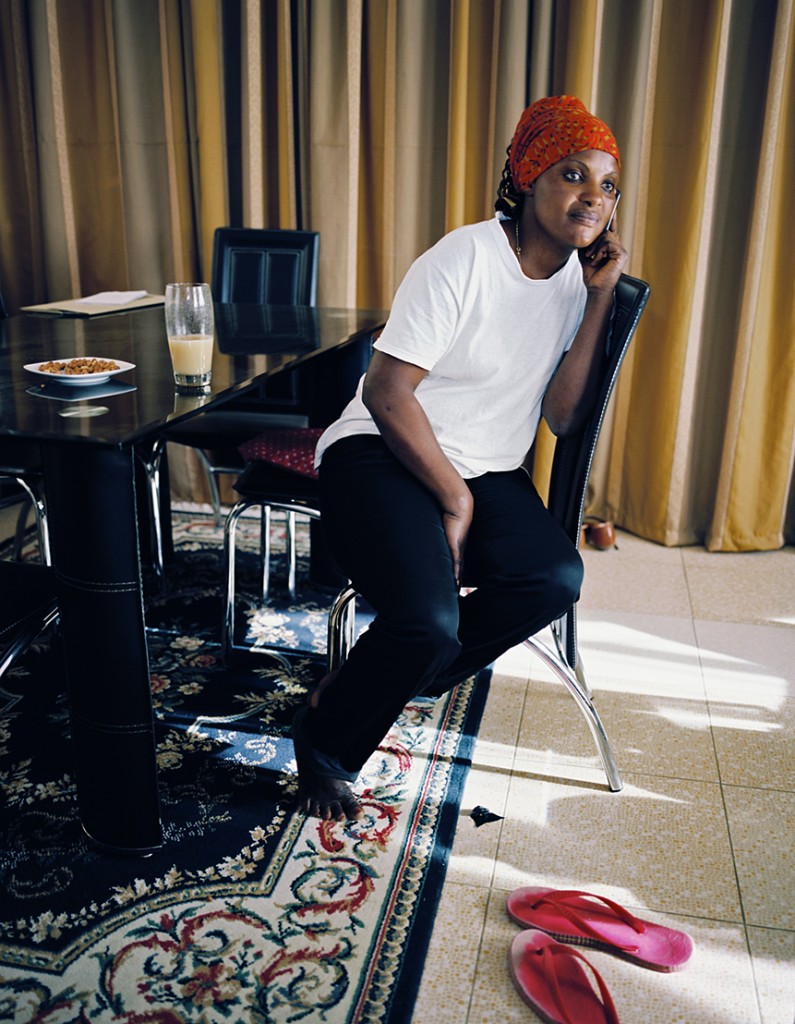

In the picture Apartment/Rita, I portrayed the cleaning lady of a temporary luxury apartment rented by my partner for work in another town. Rita behaved typically with regards to class standards. I’m white and my partner worked a lot, apparently she thought we were rich and looked up to us in a way which made us feel uncomfortable. We even felt that we couldn’t trust her anymore, because it seemed as though she’d like to take away something of us maybe. This division is somewhat common in Tanzania, though my partner maintains an equal and transparent relation towards his own personal assistant so I have witnessed this better possibility as well. It inspired me to photograph the lady in her cleaning clothes, while taking a break and sitting at our table. This was to photograph her more universal face, as if she could be an Afro-American or any Tanzanian woman, being at home and liberated from any determined or fixed position.

This inequality and division among classes has amazed me and therefore, become a source of inspiration for my work. I believe this relates to my background. The Netherlands is a multicultural and diverse country, but a class system as such is unknown and we are proud of our “poldermodel” (corporation despite differences, or recognition within pluriformity). Even today, when politics in the Netherlands is becoming more polarized and populistic, I think the “poldermodel” is and will remain deeply rooted in our culture. As a small western country with a relatively big population and a well organized social security system, we depend on a certain harmony-model and calculated risk culture. It is politically and socially safe when the majority belongs to the middle class. In fact, Rita has been a victim of my fascination, in a positive way. I portrayed her as if belonging to a middle class in Tanzania or elsewhere in the world, because, perhaps at that time, I couldn’t accept that we were divided.

Apartment/Rita © Mathilde Jansen

BJ: You have mentioned when discussing your work that International companies often impose foreign social codes and structures onto Tanzanian society. I can imagine this to be quite detrimental to the culture and society of the Tanzanian people, is there anything in particular that you have witnessed?

MJ: This is a complex issue. It’s hard to make a distinction between worldwide globalization and commercial or cultural imperialism in particular. I have witnessed, first-hand, one of the most beautiful countries on the planet. Tanzanians are aware of their impressive ecosystems, natural diversity and resources and they are not alone. What did we learn from history, simply to repeat the same? In my opinion, it’s all about money. A country willing to reduce poverty in the short term, will collaborate with foreign investors… at any price. Tanzania has rich soil but a weak position as a developing country when it comes to dealing with bigger economies, alongside long-term problems and issues as a result of corporate exploitation.

First of all, Tanzania is a huge country and life in the bush or in remote areas is totally different than that in a metropolitan city as Dar es Salaam. Second of all, Tanzanians are used to cultural diversity. Music at a Christian outdoor wedding goes together with an Islamic call for prayer, without people being disturbed or even noticing it. International companies are usually warmly welcomed in Tanzania, to stimulate welfare and career opportunities for people. Many people trust foreign commercial and cultural structures, as they have proved successful and stable. As well as this, expatriates are invited from Uganda, Kenya, South Africa and further afield. I got to know many Tanzanians as open, curious and well-willing people although, or because, life can be hard. People tend to accept possible culture clashes and act flexibly if they can have a good life or job, at least.

Many western and South African companies have social responsibility programs such as aids prevention, health care services, educational programs and stimulating female job opportunities. This is because they want to support the lives of co-workers or as part of a PR strategy.

The biggest companies of the Tanzanian market are in foreign hands, such as Chinese, South African, Japanese, Kenyan, North-American, Scandinavian and Indian. Most companies I’ve photographed have been hospitable and collaborative, opening their doors for me. All I can say about what I witnessed, should be told in my pictures. In my work I find the right language to research and express my thoughts, dreams and questions about social matters, among others.

In relation to this question and alongside my artistically staged works and collages, I’ve also made many documentary pictures. Sometimes, reality is more interesting than any artistic idea I could imagine or propose. Culture clashes or imposed structures of both religious organizations and commercial companies are part of daily life, but who cares if you can earn a living? Though I believe people do care, as ignoring peoples’ dignity and traditions can be a crime in Africa.

BJ: What was it that made you make the transition from collage to documentary photography?

MJ: I’ve expressed many ideas in collages, mostly handmade and some digital, responding critically and playfully to intercultural and sustainable actualities, in immediate ways without traveling or arranging a production budget. The friction between virtual and global media, and actual or local realities, has inspired me. In 2006, I created a body of work in which I placed African people out of images which I found in magazines, books and the internet, into my real daily life surroundings. This was to show how and where we interpret imagery, including cliche’s about poverty for example. But, in the end, I didn’t want to respond to actualities any longer, instead creating my own news or imagery and rather than manipulation with scissors, I wanted to express my ideas within the real world.

While working on a collage, I am in control of an image, representing a personal concept in more isolated ways. With regards to my manipulated images, I find it more meaningful to correspond to real, daily life happenings with an artistic approach in the back of my mind, enabling the people whom I photograph to behave in spontaneous ways or possibly, to share their ideas for the picture as well. In this way, it is a collaborative message, based on a vivid or real situation and a process of interaction. The situation develops at a location and I portray the results. This way of working is more exciting than making a collage behind a table. As I tend to capture wondrous daily life realities, I must truly believe in miracles or coincidental happenings to be able to see and catch them. I’m experimenting with and testing my own belief. Reality is my stage. The transition towards documentary photography—and in the future a further transition towards film as well—meant that I dropped collage as an activity in order to use all my creativity for art and documentary projects, made at location.

Documentary photography, as used to illustrate an opinion, fact or political article, can be seen as ‘proof’, while I like to question several points of view at one time, including my own. This is why it took me some years to make the transition towards documentary photography and I’ve had a sort of love-hate relationship with it. At the same time, I’ve always felt very connected to the essence of documentary photography (‘reality as a stage’). Today, I’ve found my own method of working, which I’d call documentary art photography.

In 2010, I portrayed a co-worker of a well established hotel at Kunduchi beach, near Dar es Salaam. The friendly, professional staff inspired me to photograph this man in a respected manner. From the reception, we went to the foyer to make his portrait. He posed with a natural comfort in the chair and the image reflects his dignity at a higher level. The co-worker could be seen as an influential man of the world, like an ambassador or a politician. This is my representation of him, in a world of daydreams and possibilities. In Tanzania, the pride of a man is of golden value.

Residence/Yusuf © Mathilde Jansen

I’d like to mention that documentary photographers often use comparable ways of subtle manipulation. For a news article about poverty, a child is situated in front of a dry or desolate landscape, in order to illustrate the miserable cash crop of the season. It is important to spread this news, but it’s important to tell the story of African pride as well. Why do we westerners focus so much on the many problems in Africa? It keeps up dependence relations, as described by people such as Dambisa Moyo by her book Dead Aid. I criticize this with my work and try to break a negative spiral by doing the opposite and portraying someone as equal or, in this case, in a world of luxury, by which he’s surrounded in his daily life. A more positive or open imagery can be seen as a tool for progress.

BJ: A question that you yourself have asked before; when you think of women’s economic power and potential, what do you picture?

MJ: Here, I’d like to mention female characteristics and intuition in general and with regards to being a Dutch woman, as situations can be so different worldwide.

Women enrich economies and societies with emotional intelligence and social awareness. They could open doors by speaking and caring openly about sustainable issues as they’re associated with long term achievements, social values and responsibilities within the community. Sustainability is a matter of the heart, in the first case; One has to feel the artificiality of an industrial chicken, before choosing an organic one for example. In the western world, we’re used to commercial market models with less room for female or so called “irrational” sensitivity.

Would a sticker saying ‘made in Congo and China’ on a mobile phone, change the comfortable experience of consumers? A sustainable way of life is sometimes laughed away as ethically correct; ideal, perfect, therefore boring and not realistic after all. However, we can expect the life of the organic chicken to be more adventurous and related to natural processes, than the industrial one. Are those people scared of their deeper feelings; thus, could women function as a role model when it comes to being in touch with your sensitive nature?

Women could advertise red lipstick on tv, but also spread the word in their neighborhoods to recycle products or support and promote good health care in political ways. They could even use their attractive, beautiful or inspiring appearance to stand for a good future for their children by being brave women or role models. Equality is something women can initiate themselves rather than waiting for it, by believing in their own power.

The visualization and realization of a healthy society and future needs an emotional awareness. It is an illusion to think a stable economy can be managed by only rational models. The abolition of the slave trade was an economically and politically unattractive development. Powerful men during that time didn’t have many reasons to speed up that process. In the 1840s, several women played an important role in the abolition of slavery in the Netherlands, by writing letters to King Willem II in a time when it was uncommon for women to be politically active. Their letters had an emphatic and social content, because the women didn’t have a commercial or business interest; they spoke from their heart only. Besides the emancipation of slaves, the letters simulated the emancipation of women as well.

Mapozi Designs © Mathilde Jansen

Several weeks ago, I became a mother. My view on life has shifted, like that of many parents before me. I now realize the impact of motherhood and natural forces on women, as a process of love, care and practical organization. Women relate closely to nature, as seen by their menstruation cycle, the act of giving birth and intuition. Their natural awareness could put a positive pressure on new sustainable developments. At the moment, I’m spending about 5 hours every day breast feeding my young baby. This is similar to a full time job, alongside my work. It is an investment in the health, emotional development and future of a new citizen. How could one determine the market value of a mother’s milk or the time to care for an elderly parent? In an industrialized society, it’s a challenge sometimes to find space for the experience of natural instincts. In rural areas women might face other problems like limited opportunities to work or to develop themselves. I believe many feminine capabilities are hard to determine as such. Lots of women worldwide combine work and motherhood, manifesting themselves via several roles within society.

It can be hard for a woman to keep breastfeeding her baby when starting work and being mobile again, which is usually after 10-12 weeks in the Netherlands. This could be seen as unnatural, although it is socially accepted. Women in industrial societies, like the Netherlands, could make it their responsibility to explain that better facilities are necessary to take care of baby’s or to make it easier to combine work and motherhood. This would implement more emancipation because women would be able to move around more freely with children. It is not liberating when a woman starts working but suppresses her frustration about unacceptable situations, like leaking breasts. Women could propose special spaces in town, where they can prepare a bottle, breastfeed or clean their baby and have a drink before being on the move again. As women are the ones giving birth, how do they organize the priorities that come along with motherhood? How can they work more flexibly and in more enjoyable ways?Many women find it exhausting to care for a family and work at the same time, though they tend to accept spending at least ten years of their life like that. How do women think and concentrate properly at work, achieve their ambitions or goals like that? How do women gain more power in society with good ideas, when they’re actually exhausted? And take care of their children? Women often blame men, but they could start to simply and gently organize their priorities better. Like flexible or personal day care; asking for an increased salary (did anyone ever try?); promotion; home offices and selling handmade product lines from home. By believing that this is possible, women might benefit more of their potential. Women could think of their families, whilst defending their own rights and social and intellectual capacities. To be a happy mum, means to be a better co-worker and more better partner too. Women, as the social chain of society, should be taken care of because, on their turn, they serve many others.

I see women as multi-taskers within private and professional realms; small and big networks, bringing along a social impact on a bigger picture or, society as a whole, with strong communicative and organizational skills, within increasingly less male-oriented economies. Why do teachers or nurses earn so little in comparison to bankers or commercial traders? It’s the responsibility of societies to acknowledge and reward feminine qualities, more. Or to enable women in developing countries to study or work. I’d like to picture a world in which men and women respect and support each other, to co-operate to the maximum extent. I picture women, not being worried about their weight or occupied with digitally manipulated beauty ideals, but experiencing their health and natural beauty. If women want to be seen, they should rise up in any way which comforts them. As a loving housewife, courageous manager or both.

Regarding social responsibility or fair trade projects in developing countries, I believe that women shouldn’t be supported in fully isolated ways because of their vulnerable socio-economic position. In the end, men and women need to manage their societies together. Those smaller communities could function as a role model in societies where men spend their salary on alcohol and other goods for instance. And, in which women work, but earn too little money to care for their children. I believe in the potential of women as part of a balanced community. Just like a troubled marriage won’t be restored if you send the woman to a therapist, by herself. Maybe it’s the potential of men to love their women more and the other way around.

BJ: What is your vision of an ideal future and how do you think we can achieve this? Or, perhaps more importantly, do you even think it is possible for us to achieve this?

MJ: I see idealism as a flexible and optimistic state of mind and ideals as a motivation to achieve certain goals, rather than a goal in itself. It is my ideal to have a transparent world economy so people are stimulated to take responsibilities for their deeds, whatever those deeds may be, as long as they come from a certain awareness. A world full of hippies, would be a boring one but a world hypnotized by a capitalist market system, is a sick one. Today, we possess the know-how to create societies where innovative technologies, social values and shared profit like fair trade are within reach. I long for a modern and green society and feel as if we move too slowly towards it. Here, we’d need some idealism to experiment and renew our systems.

To me, we live in a rather conservative, instead of future oriented society, where fear for failure sometimes dominates the urge or enthusiasm for new developments. In the worst case, we can fall and rise again. Discussions about climate change often get stuck in a scientific battle about new facts or ideas and who’s right or wrong, whilst ignoring personal questions or feelings about the waste of our industries, well-being of our planet and mankind. It’s like beating around the bush that we should be trying to protect. Besides hard talk, I wish it was more common for people to be sensitive and touched, when it comes to our ecosystems and social values. Just like art, these issues have a strong intrinsic value. We, as people, can change the structures of our economies if we’d like to do so. Buy more organic apples and those trees will grow. I believe that change comes from within, will be followed by the market and, last but not least, politics. Not the other way around.

BJ: Is there anything else that you would like to tell Her Circle readers about your work?

MJ: Joseph Beuys stated that “life is art and art is life”, meaning that society as a whole or daily realities could be seen as a creative expression of mankind. I feel attached to Beuys’ theory of Social Sculpture. Not only regarding my work, but in my private life as well.

Photography is an activity of observation, interpretation, documentation, creation and presentation. One interacts with reality and takes part of that reality. I chose to stand at the creative side of documentary photography, together with a transparent, subjective and artistic way of working. I’m open about the way I can subtly manipulate realities in my images and I do it in close collaboration with people and situations on location. It’s purpose is to portray a more sublime or meaningful moment. To do good to the inner image of a person or scenery as well, not only the outer image. I find it even more challenging to portray both, by a pure documentary approach. My documentary style staged images often seem to be realistic shots of daily life. I express my ideas suggestively and because of this, they can be hard to discover. People often aren’t aware of my manipulations and see works like those made in Tanzania, as purely documentary photography. Thus, my poetic statements on socio-political issues can be taken for real situations. This leaves room for differing ways of interpretation from an audience.

I’m inspired by the ideal of objectivism as well, as represented by journalistic media. I’m willing to tell stories based on research, actualities and my communication with people. I believe an artistic approach enables more multi-dimensional representations of happenings corresponding to several layers of reality, which could be seen as objective too. In Africa, social life and business are much more informally organized than in the Western world. By sticking to a formal way of working or objective standards, foreign photographers or filmmakers could miss out [on] cultural, and other, layers of meaning. Or they may miss out [on] their picture completely, as it’s hard to work within deadlines in countries where time seems to be less linear and more circular.

In Tanzania, I learned to shut up my big Dutch mouth sometimes and open my sensitive eyes before making any pictures at all, if I want my work to stimulate more (inter)cultural understanding. Sometimes I wait for days for a picture to take place, while observing a happening developing to a final state, step by step. I should ‘snap’ it at the right moment like taking fruit from a tree, when it’s ripe, without disturbing it’s process, because you’re in a hurry and want to push things to happen, for yourself.

During my photography and art studies, my work responded a lot to the perception and representation by the news, of the issues in troubled regions such as the Middle East and Africa. I wanted to open up and renew imagery. There’s much to say about the relationship between media and spectator. I feel a responsibility to work with intercultural issues and to refresh ideas about the African continent in Europe and the western world. I correspond between cultures and ideals and am able to open up my mind to the naive extend, without losing myself or professional purposes. A creative mindset and emotional openness let me understand my subjects more closely, as if taking a part of their life into me. It is the job of a lifetime to me.

Interview by Beckie Jones

Source: Her Circle Ezine, www.hercircleezine.com

Link: http://www.hercircleezine.com/2011/12/01/mathilde-jansen-documentary-art-photography-intercultural-communication/

See more images: http://www.mathildejansen.com/category/p-r-o-j-e-c-t-s